This post was inspired by Mr. Timothy Richards, who I had the pleasure of studying under while attending the University of Pennsylvania. His graduate-level course, “Strategic Engagement with Governments,” was among my favorite I’ve taken at any academic level.

Government is good

I don’t think Gordon Gecko would ever say it, but even he would have to admit that government and business are inseparable. There are myriad ways that the two intersect, interact, and interject in one another’s day-t0-day operations. Sometimes the relationships are pleasant partnerships meant to solve problems for people in their jurisdictions. Sometimes they are bitter battles between powerful groups who want very different – even opposite – things.

Given that government is a requirement in modern society, one would assume that businesses are investing heavily in the areas where they come in direct contact with these important stakeholders. Reader, they do not. For several years, McKinsey conducted an annual survey among executives to measure how important government involvement was to their business and industry and how well those executives feel their firms perform. What they found was fairly shocking given the conventional wisdom around this topic.

The value of engaging government

In 2013, McKinsey estimated that the value at stake from government intervention for most industries was 30% of earnings, except in banking which could be as much as 50%. This is an enormous figure – in some cases adding up to tens of millions of dollars per employee working in the government relations function. And yet fewer than 30% of executives reported that they had the government relations talent and organizational setup to succeed. Only 20% felt they were successful in influencing government policy that was critical to their business.

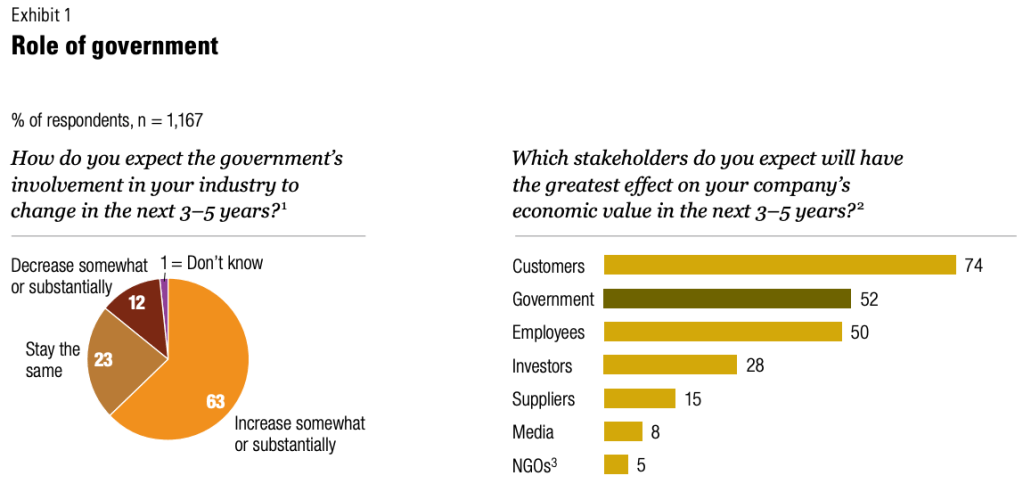

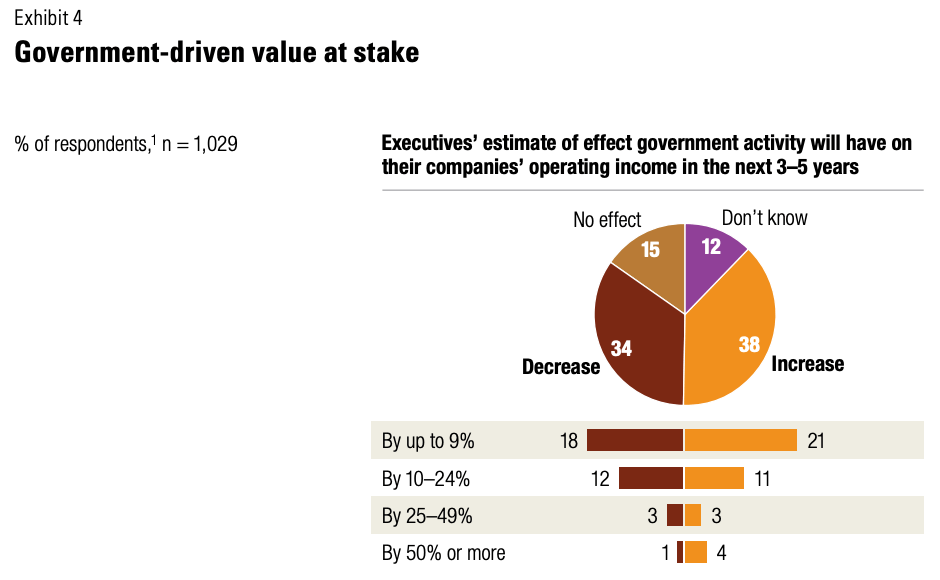

In the 2010 study, executives were asked to estimate how government activity in their industry would change over the next few years. Overwhelmingly they reported it would increase or at least stay the same (86%), and 52% felt government would be the stakeholder with the greatest economic impact on the firm. The story was similar as it relates to operating income – executives were mostly in agreement that there would be a change (72%), but split on the whether that would be an increase or decrease. Selected data is shown in the charts below.

While this study is from 2010, the many experienced, senior government relations officials we heard from in class confirmed it is still the case a decade later. In short, there is a gulf between where business knows it must be and where it currently sits as it relates to government relations work.

Improving government relations

Despite the data being a few years old, it would seem one doesn’t need to say much to convince leadership of the impact of government intervention. But how does one go about improving the function so that this value is not lost? Or ideally, leveraged into growth opportunity for your firm?

Start by understanding the current and likely future states of government intervention

You must map the current ways in which government impacts your business. This can be across several dimensions: government as partner, as customer, as regulator, or as policy maker. Once you understand the relationships, you can begin to evaluate the various touch points using your internal goals, metrics, and strategies.

For example, in class we learned about an American manufacturing firm that, after researching emerging tax credits for renewable energy technologies, made a strategic shift in their business to build out their green technology vertical. This would have been a missed opportunity without deliberate, proactive work by the government relations team.

Prioritize the issues that can be pursued

Using your map, rank your issues that you’ve uncovered by their relative impact on your business (high, medium, low) and the relative effort and/or cost required to influence them (high, medium, low). You can use a simple two-by-two matrix to draw this out visually. Are there obvious winners (High Impact, Low Cost) or losers (High Cost, Low Impact)? Note them as such and move to the “stickier” issues (High Impact, High Cost; etc). Which of these align most strongly with your goals internally? Asking these questions is essential, as you won’t be able to pursue all of the issues at the same time.

Create campaigns around each issue to make a dent

Once you have your top issues identified, you must think strategically about how to influence the relevant government officials and departments. Your government relations and external affairs staff should be able to organize the resources, tasks, and target stakeholders to support your goals. Be sure to build some flexibility into your strategy – tactics will be your saving grace if you experience any friction.

In another example, we learned about a potential production facility that would be built in a Southeast Asian nation by an American multinational firm. The firm planned to get a US Senator from their home state to make a personal call to the leader of the Southeast Asian nation, but when the Senator declined, they instead produced a joint letter signed by all of the Congresspeople from their state. This is an example of achieving the same goal, without following the strategy verbatim.

Conclusion

Government has a constant and likely growing role in every sector of the economy. In Macroeconomics 101, you are taught that government is the biggest consumer and usually the biggest producer in every country. It makes sense that 30% of earnings would be at stake, and likely much, much more indirectly as well. By creating strong processes internally to research, plan, and implement influence campaigns, companies can flip the script and proactively engage government in ways that benefit both parties.