When I started my first professional job in Spring 2012, I had no idea that Project Management was an entire industry with certifications, academic literature, and week-long seminars. I was fortunate (or not so fortunate) to never receive this training, and instead developed an approach through trial and error, and lots of great advice and coaching from managers over the last eleven years. This is an attempt to write down what I’ve learned so far, mostly through the lens of a consulting organization.

- Create a project plan – even if you never update it again.

- Where can you see there will be disruptions? For example, if your project stretches over Thanksgiving and the December holidays, you already know you’ve lost three weeks (give or take) of time to work – make sure you distribute the work accordingly.Who will miss time from the project team? Vacations, parental leave, etc. Build it in.

- Other deadlines in other projects you are not leading? Make sure to confirm them with that engagement manager / PM and plan around them, if possible.

- Set your milestone dates in advance, if possible, and work backwards.

- Where possible, ask Clients or MD / Director for any natural milestones to tie our work to – i.e., council meetings, election cycles, budget cycles, etc.

- Insist on having an internal kick-off meeting

- Make sure you have a kick-off meeting with the client, too

- All tasks should have a deadline, all deadlines should assume one additional round of revision.

- For example, we need to draft an outline for a final report on tax policy recommendations; this task needs 1) due date to the client (meeting scheduled already), 2) final version sent to client ahead of time (if applicable), 3) date to be sent to “reviewer” (I.e., Director, SME, etc.), and 4) internal meeting to discuss / brainstorm (if needed)

- Learn to love your calendar. As an analyst, meetings are few and far between. As you’ll soon read in this guide, being a great PM will require a solid number of productive meetings. At many firms, you’ll still be expected to do significant analyst-type work – often up to and including your time as a senior leader. Use the points below as a guide to get started.

- Schedule out as far as you can – when possible, set meetings to be recurring (bi-weekly, monthly, or even quarterly in some cases).Schedule your analyst tasks as meetings with yourself. If you need three hours to write a report or ninety minutes to QC someone’s analysis, put it on the calendar. If you need to stop for lunch (Author’s note: I do my best to schedule my lunch hour a month in advance), then make sure you have an hour booked mid-day.

- IMPORTANT NOTE: Once you get consistent at booking this time, anyone viewing your calendar will have a more accurate understanding of how “busy” you are at any given time. (Author’s note: This is why more senior members of the team regularly look at my calendar and say it looks more packed than theirs. The truth is they probably have just as much to do, but I look “busier” because I’ve actually tried to account for all the hours I need to do the work!!) This is invaluable when it comes time to honestly communicate your capacity to meet a tight deadline or add another project midstream.

- Adopt “Power Scheduling” principals. Like all good management systems, no one follows this 100% of the time, but in general, these guidelines help with productive work flows:

- Know yourself! When do you do your best work? Make sure you are scheduling your most important tasks / meetings for those windows whenever possible. Getting ahead and staying ahead helps here, for sure. As an example, I often start to drag around 2PM, so I will try to schedule low-value meetings during that time since I won’t be doing much work anyway.Know your team. Don’t be inflexible, and don’t say ‘I’m doing this to follow Power Scheduling!’ Just default to these choices and the rest will fall into place.Book yourself back-to-back, but not all day. Two one-hour meetings or three thirty-minute meetings is probably the outer limit of what can be productive if you are leading each one. Schedule a break in between, then go back-to-back again if possible.Monday / Friday: Internally focused days and nights. Try to schedule as many of your internal meetings on these days as possible. Reserve your evenings for time with family, friends, etc.Tuesday / Wednesday / Thursday: Externally focused days. Schedule your client meetings and internal working meetings for these days. Reserve the 9AM, Noon, and 4PM hours for yourself (sending emails, having lunch, etc). These are the target days for any after work professional / networking type events or outings. These responsibilities are very infrequent early in the PM’s career, but increase over time.Saturday / Sunday: Can be used sparingly for work. In the official Power Scheduling system, Saturday morning is reserved for closing out any items that didn’t get attention during the week. I don’t personally find this valuable except when I’m really swamped, but obviously your mileage may vary.

- FINAL NOTE ON POWER SCHEDULING: Again, it’s not an exact science. The keys are being mindful of the things you need to do each week, and making them as repeatable and as simple as possible. Once your calendar is pre-loaded with some of these “big rocks” you can fill in around them more easily.

- Schedule out as far as you can – when possible, set meetings to be recurring (bi-weekly, monthly, or even quarterly in some cases).Schedule your analyst tasks as meetings with yourself. If you need three hours to write a report or ninety minutes to QC someone’s analysis, put it on the calendar. If you need to stop for lunch (Author’s note: I do my best to schedule my lunch hour a month in advance), then make sure you have an hour booked mid-day.

- As a general rule, assume no one will do anything related to your project unless you directly tell them it is their responsibility and that it is needed by a certain date / time; even then, be sure to follow-up if you do not hear back from this person in a reasonable timeframe (silence is almost never an affirmative answer).

- Relatedly, if you are assigned to a project and no one else is obviously the project manager, consider yourself the project manager unless and until someone else tells you not to play that role.

- This would apply to tasks like scheduling, note taking, meeting agendas and follow-ups, etc.

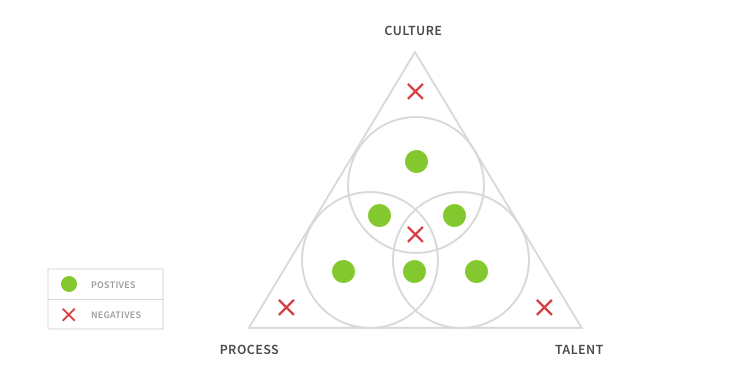

- Goals, Roles, and Budget – the most important parts of every project.

- Goals: from the client and MD / Director – what does success look like for this project? What specifically does the client need from us (i.e., capacity, guidance, a specific deliverable, etc.)?

- Roles: who is the project lead (“Engagement Manager”)? Who needs to sign off on major documents / presentations / etc.? Who leads the regular meetings? Who is the project manager (“second chair”)? Who is the analyst?

- Project Roles also apply to (and may differ from) roles related to specific documents and meetings, see more on this below

- Budget: for a given organization, this may be more about time than money – so be sure to apply your leader’s approach to this element of PM.

- Based on the scope of work, who is expected to do the majority of the work? Who else can be involved as an expert or support if needed for extra capacity? How much is the project worth – and by extension, are we comfortable going over budget for any particular reasons (i.e., opportunity for staff training, marketing purposes, helping to win future work, etc.)?

- Ship something every two weeks. It will probably need to be in draft form in many cases – this is a good thing! It forces the PM to play more of a role in creating templates or very early drafts for internal work.

- If this fits your project plan, great. If not, consider how you can have some “thing” (a topic, a draft document, a key question) to bring to each bi-weekly meeting.

- Always try to deliver your major project deliverables at these bi-weekly meetings – it saves time on scheduling and keeps your client on a rhythm of focusing on this project.

- As a result, meet with your client once every two weeks.

- Depending on the project, this may not be entirely necessary; meeting frequency should be agreed upon by your team and the client as part of the kick-off meeting

- Notes on scheduling any and all client meetings, including bi-weekly meetings:

- Always provide at least three options for dates / times

- Always clarify the length of the meeting – 30 minutes, 60 minutes, or longer, as needed (and only with Client / Engagement Manager approval).

- Always provide times in the time zone of the client (or most senior person on the client team, if it differs)

- Use calendar HOLDS when scheduling for someone with a tight calendar (I.e., most MDs and Directors); this means sending calendar invitations for each meeting window clearly labeled “HOLD – PROJECT X MEETING” and sending these BEFORE you send the email to the group you are scheduling

- Once the meeting is scheduled, delete the HOLDs you no longer need

- Meetings must have an agenda and clearly assigned roles – who will present what, who is preparing any documents to present, who is sharing their screen, etc. The level of preparation definitely scales according to the importance of the meeting, though it should always be clear

- If no clear agenda, reach out to those attending to ask for topics or to cancel.

- Meetings must have an assigned notetaker, and they MUST identify the next steps and who is responsible for each.

- Documentation must be intentional and consistent. Ideally, every activity in a project will be captured by some sort of documentation. Without this documentation, you can easily get lost or forget a critical decision. (Author’s note: This recently happened to me with a project where roles were inconsistent, and I made the mistake of not assuming notetaking responsibility. The decision I did not capture was pretty important – the date selected to launch a survey).

- Meeting notes: Every meeting should have notes taken and saved in a central location. If there were not noteworthy items in a meeting, it should not have happened in the first place!

- Emails: As a general rule, I try to not have something in email only, because it is unreliable and less accessible than a shared drive. However, for internal items or basic information sharing, it is of course an acceptable document. If you write a great email with lots of information in it, consider printing it as a PDF and saving to the client drive.

- Meetings must have a follow-up email, promptly (within 24-48 hours of meeting) with clear and direct next steps, assignments, and deadlines.

- Use bullet points to separate out the next steps

- If scheduling a meeting is a next step, consider whether to include it in this message or send a separate email to the relevant project team members

- Internal meetings – as needed, but assume you need more than you do. Meet too much first.

- Again, having an agenda is critical; roles can vary by what type of meeting – if you want to brainstorm something, prompt the team so they come prepared; if you want to present a draft of something, consider whether you need to send it ahead of time (not a requirement)

- For managing specific analysts, consider a once-per-week check-in for 15 minutes, three question agenda

- What did you work on last week?

- What are you working on this week?

- Are you stuck anywhere / on anything?

- When in doubt, send an email.

- How are we feeling?

- What did you think of that meeting?

- Where should we go next?

- Should we ask an MD / Director / Senior Advisor what they think?

- Does the timeline still feel right? Do we need to speed up / slow down / change something?