This post was originally written in September 2019 for the Message Agency blog.

Digital projects usually seek to both decrease costs and increase efficiency through the use of technology. If the choice was “either-or,” these projects might not be as attractive to decision-makers. Most want to understand the “both-and” proposition.

John Kotter spent nearly three decades on the faculty at Harvard Business School. His 1996 book, Leading Change, was an international best seller. In 2011, TIME® magazine listed it as one of the “Top 25 Most Influential Business Management Books” of all time.

While it is most commonly taught in leadership and management contexts, I find his 8-step process for managing change to be invaluable for managing projects with our clients. To paraphrase Kotter on the topic, there are two fundamental goals at the heart of most digital projects:

- Increase revenue / equity or decrease costs

- Become more effective / efficient

Many astute managers would ask the question: Why not both? Digital projects, in particular, usually seek to both decrease costs and increase efficiency through the use of technology. If the choice was “either-or,” these projects might not be as attractive to decision-makers. Most want to understand the “both-and” proposition.

Fortunately, by following some of the key steps in Kotter’s eponymous model, you can manage costs and increase the effectiveness of your digital project. Achieving this goal is particularly important for nonprofit organizations and others with limited budgets, who need to ensure a substantial return on their organizations’ investments.

Urgency, Urgency, Urgency!

Like the famous rallying cry of real estate agents everywhere regarding location, the one thing your project simply can’t do without is Urgency. The unfortunate reality is that some projects will fail for one reason or another. You’ve probably been part of projects that got off the ground but couldn’t stay the course. Or maybe one decision maker’s flavor of the week replaced a more sustained effort from years past.

Regardless of the context you find yourself in when embarking on a new digital project, it is imperative that you find a source of urgency. This can come in many forms, including:

- Executive sponsorship and support (e.g., your new ED recognizes a need to improve the website);

- Alignment with a key milestone (e.g., your organization is celebrating its 50th year in operation);

- Acknowledgement of the danger in maintaining the status quo (e.g., your website is end-of-life next year, and you need to raise funds for a redesign).

Wherever you find your sense of urgency, Kotter recommends that you should do what you can to protect it! We agree, as 50% of transformations fail at this first crucial step. Maintaining a sense of urgency means your project will be more likely to get prioritized by you and your colleagues.

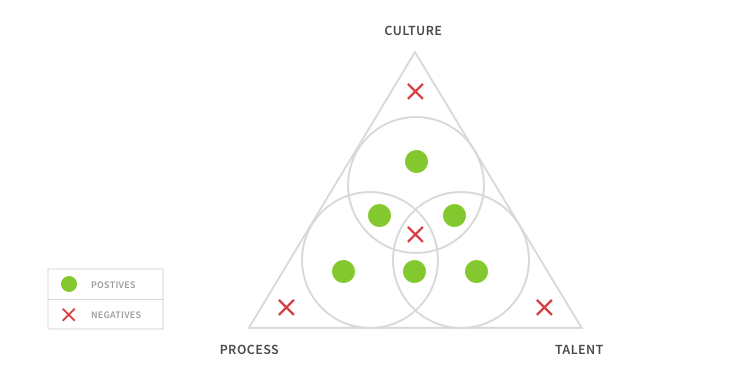

Great Guiding Coalition

Your project team is another major variable in the success of your new digital strategy, website, or public education campaign. While you need dedicated resources to manage the day-to-day of your project, you also need to go beyond the usual suspects in order to ensure success.

A great guiding coalition will include:

- Diversity in diverse forms (e.g., level, tenure, ideas, and departments);

- A strong project manager to consolidate communication; and

- Accountability to the project goals.

Accountability in this case goes beyond attending meetings and checking boxes. The project team should have the goals aligned with their own department or functional goals. Digital projects can often be considered “internal work,” but should be prioritized in the same way as serving end users.

Generating Quick Wins

During project planning, it is imperative that milestones are agreed upon early. At the same time, coalition members should be asking: “What can we show (or implement) at the end of each phase?” This evidence of change could be as simple as a list of actions taken, lessons learned, or an immediate process improvement. Quick wins build credibility and generate support for the digital project across relevant teams.

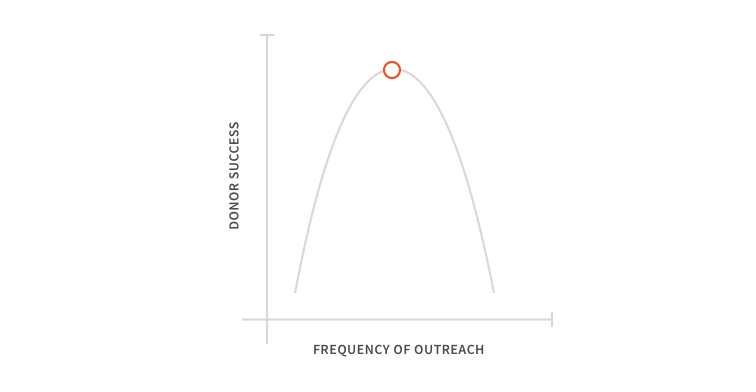

For example, if your user research uncovers that most donors are donating online, but you don’t have a link to donate on your homepage, could you simply add a donate button today? If so, you can address a specific, evidence-based need and demonstrate to colleagues that you are focused on tangible outcomes.

Sustain Acceleration, Institute Change

Your coalition is collaborating at a high level. You’ve maintained your sense of urgency along the way. The quick wins are piling up, and your digital project has become the envy of the office. So, you’re good right?

Not yet.

During the project, you’ve surely bumped up against a few barriers, or found elements of your internal processes to be restrictive. Now is your chance to consider how they might be improved. Use your success so far to address a new goal that fits the overall project vision.

For example, in creating a content strategy to drive more volunteer sign-ups through your site, you realize the intake form is not very user-friendly. To maximize the effectiveness of your website redesign, work with your volunteer coordinator to make improvements that can launch with the new site.

Getting the additional input from their department while making an update that improves user experience is a win-win. As you build momentum in your digital project, don’t overlook opportunities to fuel further positive change.

On the path to digital transformation

Kotter’s model can be applied to any change management process, but it is especially helpful for digital projects, where multiple stakeholders, complex technologies, and competing interests can quickly hamper progress. Change is always challenging, but if you follow some of these simple steps to help build trust and maintain momentum, it doesn’t need to be painful.